Jasmine stands in the back of the cafeteria, keeping one eye on the students wolfing down food as she scrolls through the emails that come in as fast as she can move them out. A text alert pops up: Mr. Fisher is having problems with Marcus again. There goes the 10 minutes Jasmine had budgeted for lunch. Not to mention the schedule coordination she still has to do for the next round of state testing. Won’t get into any classrooms today, she thinks. Same as yesterday. Same as the day before. Jasmine sighs.

I work with many school leaders like Jasmine. Some feel elevated by their work and can’t wait to get to school each day. Others feel worn down and are considering leaving the profession. The difference has little to do with the size or location of the school, student or community demographics, or even the makeup of the school board. What explains it? Purpose. For Jasmine, and so many other leaders and teachers, the urgent work of completing tasks diverts attention from the purposeful work of investing in people.

Most of us entered education because we wanted to improve students’ lives. We moved into leadership to increase our impact on students, and to support and grow the adults around us. Our purpose for being in education is centered on people. But when urgency takes hold, our days revolve around tasks, not people. This shift pulls us away from investing in meaningful time with others. And when we lose the meaning of our work, we risk losing not just our purpose, but our desire to keep leading and teaching—fueling the very retention challenges our schools are trying to solve.

We’ve known for decades that teacher self-efficacy is linked to student achievement—and it also plays a role in retention. Simply put, educators who feel their work matters are more likely to stay in the profession. If we want to increase retention, we need to invest time in people and communicate that they and their work are important and influential (Grissom et al., 2021). Refocusing leaders’ attention on supporting and growing teachers can increase retention for everyone, as leaders find themselves doing work with greater meaning and impact. But to make that shift, educators need to better understand how urgency in our environments interferes with doing purposeful work.

When Urgency Undermines Purpose

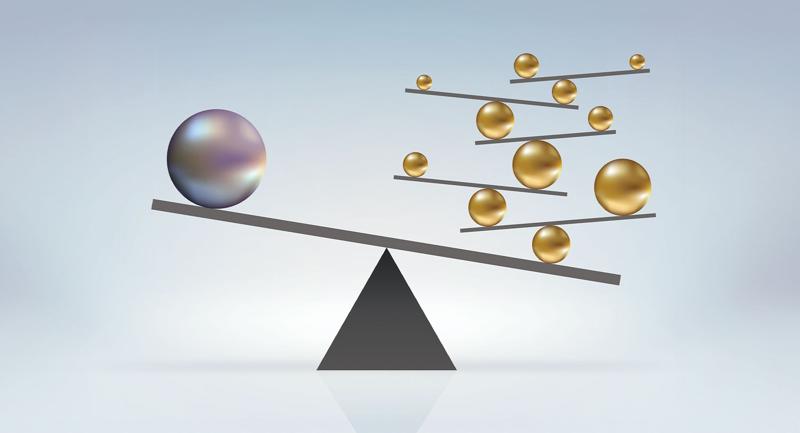

One way to better understand how urgency pulls us away from purpose is with the Eisenhower Matrix, a time management tool that helps us recognize that urgency and importance are not the same. By mapping tasks according to these two variables, the matrix (see Fig. 1) assists us in distinguishing between what truly matters and what simply demands our immediate attention.

Leaders can use the matrix to shift from urgency-driven action to purpose-driven leadership. That shift begins with awareness—recognizing when urgency is in control. From there, leaders can begin moving from managing time to managing priorities, from reacting to what’s most pressing to focusing on what’s most important. The matrix helps guide that shift, offering a practical way to make more intentional choices and protect time for meaningful work—especially the important but nonurgent tasks that can get pushed aside. In the frenetic pace of school environments, it’s easy to prioritize urgent tasks (quadrants 1 and 3) over important ones (quadrants 1 and 2). To understand why this matters, consider school leaders’ core responsibilities:

The first two—safety and legal compliance—are both urgent and important (quadrant 1) and rightly demand leaders’ attention. But the third responsibility, improving student outcomes, is more complex. Because leaders typically aren’t teaching students directly, they meet this goal by supporting and developing teachers. That work, though essential, is rarely urgent. It lives in quadrant 2.

And that’s where the challenge lies. When urgency takes over, quadrant 2 gets neglected. Instead of investing time in growing teachers, leaders like Jasmine get pulled into managing time-sensitive crises, replying to messages, and coordinating logistics. They rarely get to do the work that gives their role purpose.

Yet the work of quadrant 2 is critical. Supporting and growing teachers not only improves schools, it shows educators that they matter and their work is valued. When teachers feel seen and supported, they are more likely to stay. Just as important, when we help others know they matter, we are doing the work that makes us matter.

A Foundation for Intentional Decisions

As necessary as it is to distinguish between urgent and important, it isn’t enough. There are structural and cultural issues in schools that push teachers and leaders to attend to what is urgent, at the expense of what is important. Moving from managing time to managing priorities requires a perspective shift in how we view our days. The key here is intention. There are three essential understandings (or epiphanies) that have helped me make more intentional, purpose-driven decisions:

We can’t do everything.

Because we can’t do everything, we can choose what gets done (and what doesn’t).

Our choices reflect our values.

Taken together, these epiphanies can reframe our work from a never-ending list of tasks into an intentional dance we participate in each day, gracefully moving among essential quadrant 1 tasks and opportunities to prioritize quadrant 2, investing in people and fulfilling our purpose.

The first epiphany forces leaders to confront reality. There is simply too much to do. The job is never-ending because the needs of a school are never-ending. We could work 24/7, 365, and there would still be tasks left undone and people who need our support.

This leads to the second epiphany: If we can’t do everything, how do we decide what gets done and what doesn’t? In urgent mode, we focus on tasks and time, often reacting in the moment and making our decisions based on what feels most pressing. What if, instead of being driven by the urgent, we were driven by the important? What if, instead of spending time on tasks in quadrant 3, we invested time into people in quadrant 2?

When our actions don’t align with our stated values, the third epiphany can hit hard. For example, I say people are my purpose, but the truth is I haven’t invested enough time learning the stories of the people around me. I say I am an instructional leader, but I spend more time on email than I do with teachers.

Let’s revisit Jasmine and reimagine what her day might look like if she made intentional choices consistent with her values, while also juggling some urgent tasks.

Jasmine’s phone is in her pocket. She notices a group of students eating lunch in silence. That’s odd, she thinks, edging over to the table. “Are you all OK?” The students complain about Ms. Hooper’s science test, which they all failed. Jasmine asks a couple of questions, helping the students to reflect and learning a bit more about why the test was challenging. She makes a mental note to check in with Ms. Hooper. If these many kids failed the test, is Ms. Hooper feeling discouraged? Jasmine’s phone buzzes. It’s time to check in with Marcus before he goes to Mr. Fisher’s class, where he has been struggling. After that, she’ll shut her door for 20 minutes to eat lunch, then work on the testing schedule before circling back to check in on Mr. Fisher.

Jasmine’s day isn’t perfect, but it’s purposeful. By pausing to talk with students, checking in with teachers, and protecting time for what matters to her, she’s making decisions that reflect her values. In doing so, she’s shaping a school culture where teachers and students—not tasks—come first. And that’s the kind of culture where people are more likely to stay.

When urgency takes hold, our days revolve around tasks, not people.

Urgency vs. Importance in Practice

Shifting from urgent leadership (centered on tasks and time) to strategic leadership (centered on people and values) doesn’t happen overnight. We can’t expect to instantly escape quadrant 3, but we can take small, intentional steps toward acting with purpose. Fortunately, most school leaders are given daily opportunities to support and grow people—and each of these interactions involves a series of choices. While the following four choices may seem small, together, they shape how we lead.

Will I show up as the best version of myself?

When we choose to show up fully, the world slows down. Admittedly, we may not show up as our best selves in every interaction. After a sleepless night or long day, our capacity may be limited. That’s OK. What’s critical is that we take a moment to make a conscious choice about how we show up. Making the choice is more important than the choice we make. In other words, being intentional in our choices is what leads us to make better choices.

Will I be fully present?

Full presence means giving someone our two most important resources: our time and attention. It requires us to quiet our mind and to focus wholly on the person we are with. In being fully present, we communicate to the other person that they are, in that moment, the most important person to us. When we shut out all distractions and noise, we create a safe and welcoming space. Holding this space is the key to fulfilling our leadership purpose.

Will I ask questions?

This choice can be deceptively difficult to get right. As teachers and leaders, we are taught to share knowledge; to fix problems; to direct, advise, and nurture. We are conditioned to believe that all these things require us to open our mouths—to fill a space with our thoughts and ideas, rather than create space for other people’s voices. Asking questions gives others room to reflect and contribute. Even simple questions—“How are you?”, “What went well?”, “Is there anything you would do differently next time?”—can become invitations to think deeply and connect.

Will I listen?

After we have asked questions, we make the final, and possibly most difficult, choice. If we are not constantly waiting to jump in, will our mind wander? Will we begin worrying about the next meeting, the emails piling up, or tomorrow’s interview for the new instructional coach? Or will we truly listen? When we truly listen, we offer the gift of our full attention in a world that rarely slows down.

These choices—showing up, being present, asking, and listening—communicate to people that they matter. Remember:

When we show up as our best selves, we communicate to people that we see them.

When we are fully present with people, we communicate that we value them.

When we ask people reflective questions, we communicate that we trust them.

When we listen, we communicate to people that we hear them.

Importantly, when we do these things for others, we are also doing them for ourselves. We, too, reflect and grow. We experience being valued and a part of the school community. When we—teachers and leaders—grow, feel valued, and feel connected, we are all more likely to stay (Louis et al., 2016).

Leading with Purpose Every Day

We read earlier how Jasmine might reframe her day by being more intentional in her interactions with students and teachers. As she invests time in people, they will grow. Over time, her teachers’ skills will improve. Students’ decision making will get better. And Jasmine will be fulfilling her own purpose by helping teachers fulfill theirs.

So, what about you? What might it look like for you to reframe your day? There are several simple structures that can help you bring more intention to your daily interactions, helping you lead with purpose even on your busiest days:

Begin with intention. Ideally, we intentionally decide to show up in every interaction, but it might be easier to begin by identifying one to three people for whom you will actively choose to show up, ask questions, and listen.

Plan around priorities. Try organizing your day around a priority list instead of a to-do list. For example, prioritize checking in with a specific teacher or student, or observing a lesson. Schedule these priorities, then fill in around them.

Reflect daily. At the end of each day, ask yourself: Was I intentional? Did I create space for others? Did I act on my values?

Keep the matrix visible. Post a copy of the Eisenhower Matrix in your workspace as a visual reminder to focus on what’s important, not just what’s urgent.

Small, intentional acts like these not only make your work more meaningful and fulfilling, but also communicate to others that they are seen, valued, and heard, helping to build the kind of school culture where people want to stay. Reconnecting ourselves and others to the purpose behind the work we do is key to building resilience and increasing satisfaction in an all-too-demanding profession.

Reflect & Discuss

Which quadrant 2 activities (important but nonurgent) do you tend to neglect—and what would it take for you to prioritize them?

Which of the four strategic leadership choices (showing up, being present, asking, and listening) do you find most challenging and why?

What’s one small, intentional shift you could make this week to better support a teacher?