For most of my elementary school years, my parents and I believed I was a struggling math student. Math was hard for me. The numbers did not make sense. I was not good at memorizing math facts or understanding word problems. I remember us ceaselessly reviewing flashcards and practice books at home—my parents worked just as hard as they were pushing me to work. My father would come home and sit with me at the kitchen table in his postal uniform to help me with my math homework. But I was still always placed in the lowest math groups in my classes.

That all changed in 6th grade. The school placed me in Mr. Bryant's 7th grade math class because of over-crowding in the 6th grade class. Mr. Bryant may have been my first male teacher—he definitely was my first Black male teacher. Mr. Bryant called his students "Mister" and "Miss," and he expected us to give respect and take ownership of being respected. He was a graduate of North Carolina A&T State, the historically Black university that I would later attend, and he told us that was where he'd learned greatness and became passionate about teaching.

From day one, my experience in his class was unlike anything I'd ever experienced in school. The learning was real for me. Mr. Bryant taught math standards in the context of people, places, and things I knew personally. And I was seen. I existed. It felt great to be a learner in this class—to find inspiration from real life, not a dog-eared textbook. I do not remember ever having a textbook in Mr. Bryant's class. Instead of using "Aunt Sally" in the common mnemonic device to learn the order of operations (parentheses, exponents, multiplication, division, addition, subtraction), Mr. Bryant taught it to us as "Please Excuse My Dear Aunt Shaniqua." He said he did not have an Aunt Sally. I didn't either.

In geometry lessons, he used the angles of the homes located right outside our classroom window in our Southeast Raleigh, North Carolina, neighborhood, an area that remains largely Black occupied amid gentrification. We took imaginary trips to the store at the corner of Lenoir and Haywood Streets or visits to the farm (Mr. Bryant's family, and many of our families, had farming roots) to learn about ratios, interest, proportions, and affordability. He also told us about J.W. Ligon, the Black man for whom our school was named, and Sheriff John H. Baker, Jr., an alum of our school who lived in my neighborhood, formerly played in the National Football League, and in 1978 became the first Black sheriff elected since the Reconstruction era.

I loved math for the first time and quickly gained confidence and proficiency. I went from believing I was a struggling math student to winning countywide and statewide mathematics awards. I was equipped for the future. The math knowledge that I had developed would last long after my time in Mr. Bryant's class. At the beginning of the next school year, Mr. Bryant advocated alongside my parents for me to be placed in the 7th grade algebra class. When I was finally able to join the class after several weeks of advocacy, I was the only Black kid enrolled.

Mr. Bryant changed the way I thought of math and of school. He is largely the reason why I became a math teacher and am an educator today. I wanted to ensure that other students knew they too could thrive and enjoy learning at school without having to fight for what was due to them. I wanted to create equitable learning experiences and opportunities for all students.

Breaking Down Barriers to Success

What made Mr. Bryant so effective as a teacher—what made him an example of equity in action? A primary reason was his focus on relevant curriculum. We often define educational equity as giving students what they need to support their success. There are times it is defined as meeting students where they are. With what we know about education today, educational equity is also about breaking down the barriers to success. We know equity is our issue, because we have academic standards that are set to ensure equality, yet we have Black students who on average perform much lower than their white peers. In fact, according to the "2011 Black-White Achievement Gap Report" from the National Center for Education Statistics, Black students' performance on standardized assessments is even lower in schools with larger populations of Black students, whereas the achievement levels for white students do not vary whether in schools with larger or lower populations of Black students.

My experience in Mr. Bryant's math class exposed me for the first time to educational equity. It would be the model I would carry with me into my own classroom when I became an educator. The curriculum we were provided under his leadership was more than a set of standards and subsets of skills generically outlined in a pacing guide that the state believed we needed to know. Instead, content was adapted to the context of who we were as students. With our lives as context, math was no longer something we were forced to do within the frame of a world we did not know. Math became what we lived out every day. Seeing ourselves in the math we learned meant enjoying math talk in our homes and other community spaces, practicing math innately in our environment, and sharing what we learned when we saw it taking place right before our eyes and in our world.

This is exactly the kind of growth and achievement we should seek in our classrooms daily. Math mattered because we mattered. As a result, we became more than proficient; we were prepared to be anything we wanted to be.

The official curricula educators are given are built with the intent of ensuring a set of standards are delivered "properly." The "appropriate" skills are taught. Algorithms are applied to reach an "understanding of a concept." The problem is that curriculum designers do not always take equity into account. The curricula purchased by districts and schools are often prepared in a standard form to ensure equal access for learners. The content and the manner in which it is presented are designed to be relevant in ways that are very generic to improve their marketability. However, the students who sit in our seats are not standardized. They do not come to school with the same preferences, identities, experiences, contexts, or cultures. To truly be equitable, any curriculum we present to our students must honor who they are. It rests on us, as educators, to build equity within the curriculum we teach so that we can reach each student.

This does not start with the teacher instructions, pacing guide, or scope and sequence, though these can be important in ensuring understanding and consistency. Building equity through curriculum begins with understanding the cultures and identities of our students. This is more than relationship building—it is about learning what our students value, their cultural norms and traditions, what they like and enjoy about themselves, and the associated historical and societal contributions attached to these perspectives. Beyond what we believe or think we know and have experienced, this knowledge comes directly from students and families. And we, as educators, need to listen.

Integrating Culture and Family

What's the most important thing I need to know about you? This was the last and most powerful question on the first-day interest inventories I would give to my students when I was a math teacher. What is the most important thing you want me to know about your child? was the first question I asked parents on their open house exit ticket. This was the foundation of me getting to know what students and their families valued.

Teachers shouldn't pry into personal matters, but they should ask students to bring themselves to the classroom in ways they are comfortable sharing. Just as Mr. Bryant used the community around us to highlight math strategies, teachers need to show all students how the curriculum can build on their lives and interests. One strategy that opened windows for my students and their identities was the weekly current event. Students had a standing assignment to look through any article, journal, magazine, comic, or other publication and identify how what we were learning was incorporated. On Fridays, they would present what they found, describing the math of the piece and why they chose it. By Monday, their article and accompanying explanation were posted outside the classroom door.

This information-gathering allowed us to learn together. It was about more than just understanding their interests. It provided an in-depth insight into how these interests developed; what current events were most important to students; how they reasoned and connected with mathematical concepts; and even more, how these concepts made sense in their world.

The premise was getting students to share more about themselves in their own words. So often we seek to understand only what we want to know about other people, centering on our comfort as the foundation for building relationships. As educators, learning values and identities is about decentering ourselves and creating a comfortable place for students to understand their value within the learning community.

When students do begin to reveal themselves, it is up to us to build on that knowledge—and invest in their cultures. When they encounter content that resonates with them, they are comforted by teachers who are aware, can elaborate, or even allow students to share the significance and relevance of the learning in their own words. Even more: When students see us visiting their places of worship, taking part in their community celebrations, or otherwise engaged in aspects of their lives outside of school, they know they are a part of a learning community. They are seen. Their identities are affirmed and given space to develop.

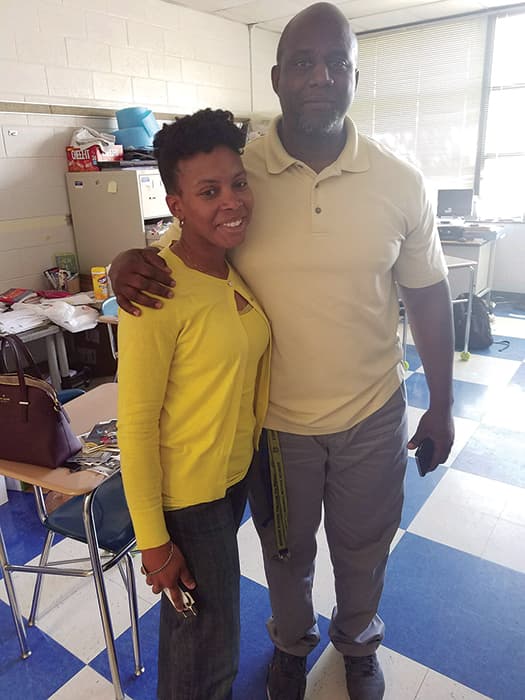

Chaunté Garrett and her former math teacher and mentor Chris Bryant. Photos courtesy of Chaunté Garrett.

Provide Role Models

Teaching about historical and societal contributions of people from the students' culture and identity is another way teachers can create context in the curriculum standards. I wonder how much differently I would have felt about my math ability if NASA mathematician Katherine Johnson was not such a hidden figure back then. I think about how challenging trigonometric trajectories, exponential functions, and calculating derivative variations were for me. What if I had experienced the inspiration that comes in knowing there was a Black woman who was not only able to do math that was beyond most people's capabilities, but was changing human history in the process?

Have we assumed that children will not want to learn about these important Black figures? Or do we not know for ourselves how to include them in our teaching? So often educators are well-intentioned, yet harmful, when they assume that playing rap music or using sports examples are the most effective ways to relay content and build relationships. These activities all have their place, but we also want to be careful that we do not lead with assumptions and commit malpractice by assuming identities or imposing identities that are not relevant to the students we serve. Equitable and intentional curriculum-building means taking the context provided by our students and aligning it to the curriculum standards. This allows students to recognize themselves, their way of life, and the contributions of their shared identities within the fabric of our history and as a valued contributor within society.

The election of Vice President Kamala Harris, for example, can provide context for social-emotional learning for all of us. The impact of having the first female, Black, multiracial, Asian as Vice President of the United States can help students to understand that there is greatness and opportunity within themselves. To hold conversations about such changemakers is not playing politics. It is about recognizing the students sitting in front of you and helping them understand the significance of important historical moments.

At the same time, context should not ignore adversity. In our school communities, many of us openly discussed the protests with our students after the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor to help students develop pathways to make the changes they seek and need.

We also need to provide learning that is relevant and applicable to our students' lived experiences. One of my favorite projects to assign as a classroom teacher was an analysis of academic achievement gaps during our probability and statistics unit. We analyzed the achievement data for our entire school as well as subgroups. The data was relevant to them, and many of them owned it. Students were able to "notice" and "wonder," and for Black and brown students, they were able to tell their stories in relationship to the data. Even though the data showed achievement gaps, students saw firsthand how standardized data does not paint the most important picture of success for them personally or for their peers. They were able to see that there were different experiences for students of color within educational institutions. It also gave them an opportunity to address and redress stereotypes that non-Black and brown students had already learned.

Bringing awareness to social issues in the context of the math concepts we were studying left them equipped with skills and background knowledge to think critically and challenge inequities they may face or see in action in the future.

It should be noted that this kind of work needs to be ongoing. Students deserve to see themselves as a valuable part of history and a valuable part of society throughout the year, not just on dedicated days. This is not the time to teach random facts to check the box of equity and inclusion. This is about an intentional, sustained commitment to righting an egregious set of wrongs that has lasted for centuries and threatened our country's soul. White students are affirmed daily; texts and standards are routinely centered around Eurocentric ideas and history. Black students and other students of color become more and more disenfranchised by the narrow opportunities to know themselves in the context of the world they currently live in. Equity requires being intentional about building curriculum in which the standards are learned within the context of our students' lives.

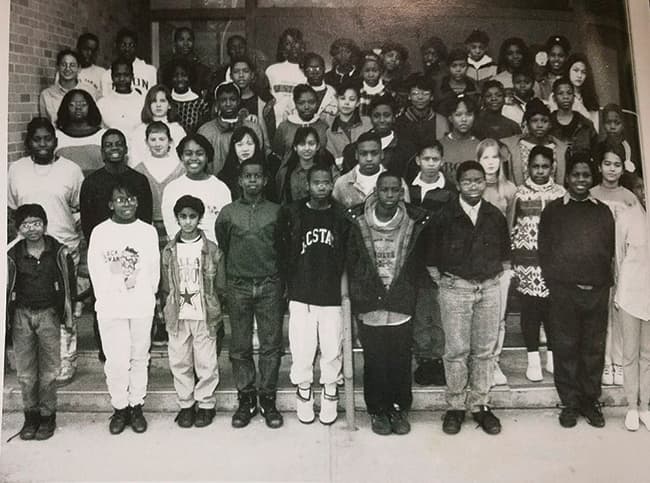

Chaunté Garrett, pictured in row 1, second to left, and her classmates in Mr. Bryant's Math Science Education Network class in 1993.

Exclusion and Inclusion

The most powerful outcome of intentionally building equitable curriculum is the elimination of exclusion. Exclusion is the act of leaving someone out of something. When context doesn't drive the curriculum, exclusion is what students of color experience daily. Before Black students ever sit down to take a test, the feeling of being alienated serves as a barrier to their success, perceived and actual. Classrooms must become places where opportunities for exclusion no longer exist; where what is inherently separatist no longer prevails.

Eliminating exclusion is not the same as inclusion, however. Both exclusion and inclusion are rooted in the idea that someone has the power to leave someone else out. In a world, in a country, where everything is built upon multicultural ideas, perspectives, and experiences, no one should have the right to exclude; yet some hold privilege to include. By bringing students' contexts into the curriculum, educators act upon their responsibility to ensure every student has space and value within their classroom and school communities.

It was not until Mr. Bryant's class that I was able to realize the space and value I possessed as a student and within the world. In Mr. Bryant's class, I was able to "see" myself all year long, not just specified times of the year. The history that our family cherished was on display and up for discussion daily. The values and choices my family made for me were the very foundation for which my learning took place. We were appreciated, celebrated, and affirmed.

Our students have lives that should have a place and space within our classrooms and serve as context for the work we do. Being intentional about understanding and providing context to drive curriculum standards can establish more equitable conditions needed for each student to succeed. This world will not change fast enough to guarantee that the students in our classrooms will not be hurt by it. But the curriculum we deliver can empower students with the knowledge that the world will change because they are a part of it.